Is Christianity an Eastern Religion?

Answering this question teaches us much about the West, our past and our future, as well as the true meaning of traditionalism

I recently published a video exploring ‘lost’ Westerners who adopt Eastern spiritual traditions—or at least the softer parts—due to the modern West resembling something of a spiritual desert. The video garnered interesting responses, chief among them the claim that Christianity itself is an Eastern tradition.

This issue caused much debate in the comments, so much so that I originally intended to make a follow-up video, however, once I started jotting down some notes I realised this was a fascinating and complex issue that’s better off dealt with via a Substack piece, so here we are.

Off the bat, it seems obvious that Christianity is an ‘Eastern’ tradition. It stems from the East, after all.

That said, it’s been embedded at the heart of Western Culture for so long that one cannot divorce the West from Christianity, either. Further still, a Catholic may well claim that Christianity is neither Western nor Eastern, but ‘universal’. ‘Universal’ is the etymological meaning of ‘Catholic’, by the way, the word Catholic stemming from the Greek ‘Katholikos’, a combination of the words ‘kata’ (concerning) and ‘holos’ (whole) (1).

In a sense, you could say Christianity is both Eastern, Western and neither, but understanding why this is offers us an opportunity to understand traditionalism, as well as the culture of the West.

A Wanderer in the Desert

The above painting, The Temptation in the Wilderness by British artist Briton Rivière (2), is a personal favourite of mine as it speaks to the heart of the Christian spiritual journey. I will refer to this piece at the beginning and the end of this article to articulate key points concerning the Eastern/Western character of Christianity.

To begin with, let’s state the obvious—Christ is in the desert, an unmistakable (Middle) Eastern landscape. I’m sure someone out there will be eager to state there are deserts in Europe, such as the Tabernas in Spain, but broadly speaking the desert is not a normative part of European geography.

This directly affirms the claim that Christianity is an Eastern religion because it’s from the East—Jesus was born a Jew in Roman-controlled Judea with a lineage charting back to the expulsion of Adam from the Garden of Eden. Yet Jesus is not only physically from the East, but also part of an Eastern tradition (Judaism) and part of its ‘blood’ and mythology (via his genealogical connection to Adam).

Further still, even when we look at the early days of Christianity, from St. Paul to the Church Fathers, these too were men of the Semitic region, far from strangers to the ‘desert’ way of life.

Case closed. Or is it?

While it’s undeniable the roots of Christianity lay in the East, the key question regarding whether Christianity remained an Eastern tradition relies on what happened to Christianity once it was taken up in Christendom, most notably, in the Roman Empire.

Perennialism & the Institution

The first reason we cannot call Christianity purely ‘Eastern’ is because it’s hardly unusual for a region’s mythology to lay outside its geographical borders. Take the English patron saint St. George, for instance, leftists are eager to remind us plebs that St. George emanated from modern-day Turkey (3) every time St. George’s day comes around, as if that’s proof enough for a policy of mass migration in the millions to render the natives a minority in their homeland, as well as a justification for a multiculturalist state policy that undermines the prominent role of St. George himself.

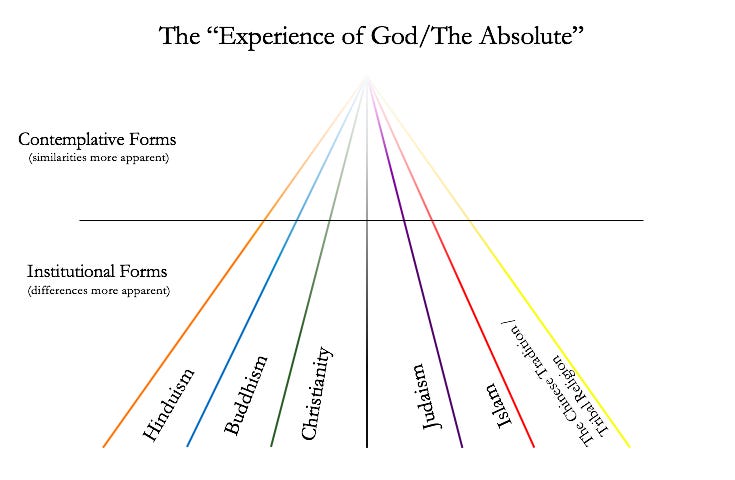

Yet the interpretation that Christianity is Eastern misses the core dynamic concerning how a tradition functions. Regular readers may have seen me use the below diagram in prior pieces, yet it’s worth using again as it’s a handy way to understand tradition, religion, spirituality and culture simply:

As you can see, all religious traditions begin with an experience of ‘God’ or ‘The Absolute’, as yet, these mystical experiences aren’t codified into any religious or cultural forms, they are purely experiences of prophetic figures pointing to the ‘timeless’ Now.

The diagram helpfully informs us that these experiences are ‘contemplative’ rather than ‘institutionalised’, and this is why we find such stark similarities between the teachings of mystics and contemplatives of different traditions, most of whom have had no interaction whatsoever:

The eye with which I see God is the same with which God sees me. My eye and God's eye is one eye, and one sight, and one knowledge, and one love.

Meister Eckhart, German Christian mystic (1260–1328)

I searched for God and found only myself. I searched for myself and found only God.

Rumi, Sufi poet (1207–1273)

Consciousness is indeed always with us. Everyone knows 'I am!' No one can deny his own being.

Ramana Maharshi, Indian Hindu sage (1879–1950)

I am that I am.

The Burning Bush (speaking to Moses in The Old Testament, circa 1514 BCE)

The above quotations come from differing traditions, yet all speak to the same transcendent mystical reality—yet is that Eastern or Western? Such questions are meaningless in contemplative matters as they are questions rooted in the physical, and mental world of man, we can only make such inferences once such teachings have been codified into religious and cultural traditions—that is ‘institutionalised’.

Unlike contemplative spirituality, the process of institutionalisation is unique because those who codify the revelations from the hearts of their prophetic founders are unique peoples, with unique biologies and histories, in unique times.

Herein is a common misconception liberal spiritualists often fall into. They assume because contemplative forms of spiritual experience mirror one another that all human, cultural, historical and biological factors can go out the window and we can all revel in ‘One Love’.

A noble aim, perhaps, yet one often ignorant of the fundamental nature of human beings, human cultures and the precarious balance upon which our societies rest. Of course, such ideas also stem from their own post-religious New Age spiritual traditions in turn.

The Western Tradition

Given we now have a system with which to understand the process of ‘institutionalisation’, we can begin to explore what makes Christianity uniquely Western, or should I say, what makes Western Christianity unique given there are other interpretations (Eastern, African, Oriental, and so on).

Western Christianity began (institutionally) via its adoption by the Roman Empire under Constantine the Great in 312, and with that adoption, Western Christianity took on a particularly Greco-Roman flavour. This is particularly true concerning philosophy, logic and academia. This is chiefly due to the impact of figures such as Plato—although his work is arguably closer to an ‘Eastern’ Christian interpretation—and especially Aristotle, who was a major influence on Thomas Aquinas and the Scholastics, a grouping of medieval Christian thinkers who sought to reconcile Christian theology with classical and late antiquity philosophy.

It’s important to state here that Western and Eastern Christianity, that is Catholicism (and latterly Protestantism) and Orthodoxy, to this very day are marked by a focus on intellectual reasoning in the former and mystical experience/tradition in the latter (5).

While the blend of Christian theology and Greco-Roman philosophy and culture created a rich philosophical, scientific and artistic framework in the West, it has also been argued that it is this very focus that’s created the peculiar materialism and individualism we have today (6).

We find such a view as represented by the author of the famed Decline of the West, Oswald Spengler, a German historian/philosopher and scathing critic of modernity. Spengler saw early Christianity as part of a ‘Magian’ frame, that is, from the world of Persians, Arabs and Jews (could we say ‘people of the desert’?) yet as Christianity became integrated into the Roman Empire it was ‘Germanised’ (7).

For Spengler, the Germanised, or ‘Faustian’ spirit of Europe struggled to reconcile itself with early Magian Christianity, with the Faustian spirit triumphing with the advent of the Crusades. H. Stuart Hughes explains this below (8):

…Christianity—not the original Church of the Magian world but virtually a new religion in which the dynamic morality of personal atonement and the intensely human cult of the Mother of God have driven out the gentle, tranquil ethic of selfless fellowship with Jesus exemplified in the primitive sacrament of baptism. This driving, aspiring faith gives to the springtime of the Faustian spirit a quality of high tension.

While Spengler’s views are more complicated than I lay out above, it is if nothing else, an example of how religions and spiritual traditions are intertwined with the spirits of new groups and cultures, thereby rendering ‘new’ denominations unique to a people and region.

As Christianity has grown around the world, we see this process happening on a more granular level. For instance, is this Mass in Mozambique the same Christianity as a village service in, say, Chipping Norton, Oxfordshire, England?

Is Christianity Western?

At the top of this piece, I stated we’d return to Briton Rivière’s The Temptation in the Wilderness, and now we have an understanding of cultural uniqueness we can read the piece in a new way.

What we can see via the benefit of the Western artistic canon is a symbology of our collective morality. We see Christ—the figure of innocence in an off-white robe (presumably symbolising the challenge of his purity)—stuck between the two worlds. He sits on the earth, grey, dark and brutal. However, if we loosen our logical minds, we could interpret it as Christ sitting on the ocean given the wavelike structure of the rock formation.

Whichever way you choose to read this, the message is clear, this is a theme we can all identify with—being tempted by material pleasures. Such trials can be arduous for us all and it’s not always easy to do the right thing in this regard. We can see the burden is wearing on Christ via his bowed head and tired pose, yet we also see great hope in the piece, a hope that sings in Christ’s heart despite the sufferings and darkness of this world. That is the radiant, golden sky behind him—Rivière opted not to paint a neutral blue sky, but instead a heavenly glow symbolising hope beyond this fallen world.

The messaging here is central to Western mythology—we must face the arduous challenges of life striving not to be corrupted by the darkness of the world, but instead ‘follow Christ’ to the promised land. That land is not so much a location, but a state of inner contentment emanating from fidelity to one’s soul.

This is the Western Christianity of our forefathers, and this, whether you view it literally or symbolically, is what the West and Westerners need if they are to reclaim their vitality and restore moral and social order once more. In closing, is Christianity an Eastern religion? It both is and it isn’t. Yet what matters is the soul-sustaining mythos, a path of redemption for the soul, and the unity of our people.

References

1: https://www.catholic.com/magazine/print-edition/what-does-catholic-mean

2: The Temptation in the Wilderness, Briton Rivière: https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/the-temptation-in-the-wilderness-briton-rivi%C3%A8re/-QFxtTGDSmsIQw?hl=en

3: Where was St. George from? https://www.ourmigrationstory.org.uk/oms/the-migration-of-the-legend-of-saint-george

4: The Perennial Philosophy: https://viaperennis.wordpress.com/the-perennial-philosophy/

5: Beyond Bells and Smells: The Gap Between Eastern and Western Christianity: Read more here

6: Materialism & The Liberal Man: https://joyintruth.com/materialism-and-the-liberal-man/

7: Spengler, Oswald, The Decline of the West. New York: A. A. Knopf, 1928

8: Hughes, H. Stuart, Oswald Spengler: A Critical Estimate. 1991.